Ron Currie Jr. would say everything. To some extent, this is true: everything could matter. As scientists how do we identify what does? And prioritize the things that do?

We live in a society where criminals are innocent until proven guilty, hypotheses are possible until proven wrong, and it seems like nothing matters until it does. Andrew shared with me an article this week on biases in scientific publications that discusses the trends of which we are all aware: negative results don’t get published, sex of subjects is rarely considered, and temperature and potentially important environmental factors are never reported. I agree with the author of the article that this is a problem. Much money and resources are likely being wasted testing hypotheses that have repeatedly given negative results. Negative-result experiments rendered their pursuers paperless while leaving future generations of scientists ignorant of what hasn’t worked in the past and what pet hypotheses they should get rid of before starting. When we suppress the sharing of negative results, I think we do a disservice to the community and forget the original rationale of starting the experiment. Experiments should not be started unless there is proper reasoning behind the hypothesis. Ethics should not allow animal models to be used if sound rationale were absent. This being the case, negative results should be informative and thus a helpful contribution to our field. However, as in journalism, television, and (most likely) life, our thirst for sensationalism quells that which we find boring. Negative results can be boring.

Boring-ness aside, there seems to be something else driving trends in research. We want to publish things that matter which brings me to the title of this post. What matters?

More and more review articles seem to be a call to arms for more complex models to consider parameters we previously ignored. Environmental factors, life history, age structure, immunity, social grouping, stress, the list goes on. If everything could matter, what matters most?

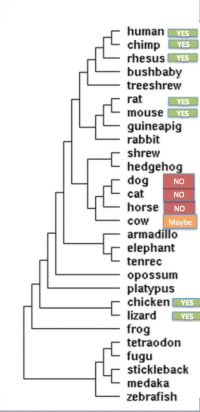

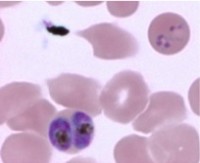

I think physicists have been struggling with this question since their field began. In Newtonian mechanics, if we knew exactly what mattered, we could theoretically predict every outcome every time. Because we don’t know what matters, we replace knowledge with probabilities based on past outcomes. In other fields of science, we theoretically should be able to predict the future if we know all the parameters at play (unless you are in the Heisenberg camp). The problem is figuring out the mattering from the not-mattering. In malaria, we don’t know exactly what matters in determining whether or not an individual will get sick. Until we do, how do we know what to report? How much of a problem is it that many studies have biased sex-ratios, poorly describe environmental conditions or use stable temperatures?

I think a solution could be found in doing more simple science to establish what matters most in the majority of model systems, and also in establishing better standards of reporting experimental subject and design details, especially by making use of online supplements. When we don’t know what could be important, I’ll agree with Mr. Currie and assume that everything matters.