I have personally always wondered why anyone would be against genetically modified organisms (GMOs). GMOs, to me, have always seemed like the inevitable next tier in the Green Revolution, and so I often go out of my way not to buy products that advertise “GMO-free” on the label. But I’ve never actually done any research into why people object to GMOs. So I finally did some research. Granted, not enough research to write a paper, or even enough to necessarily have a well-informed opinion on the topic, but it is probably enough for a blog post.

The benefits of GMOs are fairly obvious. Through genetic engineering, it is possible to increase crop yield, increase crop stress/drought tolerance, increase product longevity, reduce pest management issues, and grow crops on land previously thought to be non-arable. Taken together, these factors increase overall production and decrease waste. Good.

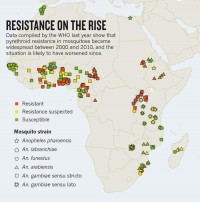

There are, however, at least three legitimate potential issues with GMOs as well. First, insecticide genes inserted into crops could potentially transfer into human gut microflora through the process of horizontal gene transfer, potentially leading to the transcription of insecticides in the human gut. I highly doubt that an insecticide-producing gene would grant any benefit to bacteria in the gut, and so the expression levels of insecticides will probably be low. It does, however, seem to me that there should be some oversight to ensure that only human-safe insecticides are produced by GMO crops.

Second, patents on GMOs severely restrict farmers. My understanding is that it is currently illegal for farmers to plant seeds from patented GMOs grown on their own land, and that these farmers must instead repurchase seeds each growing season for annual plants. Although this is a potentially important political issue, it isn’t really a GMO-issue. It is instead an issue with our current intellectual property laws. The exact same issue would occur for non-GMO crops if it were possible to patent them as well.

Third, and this is the most legitimate claim in my opinion, depending on the genes that are inserted, GMOs might cause allergic reactions that are unforeseeable by the consumer. A consumer allergic to peanuts can avoid purchasing products that contain “peanuts” in the list of ingredients. That same consumer, however, might have a hard time avoiding GMO crops that contain the allergenic peanut gene, if the use of peanut genes is not disclosed in some transparent way. How to disclose a full list of genes and gene products seems like a non-trivial challenge with current technology, and so I can concede that for people with food allergies, avoiding foods that contain GMOs might be reasonable. But since I don’t have any known food allergies, I think I’ll try to stay foods-labelled-GMO-free free.