Every once in a while I read something that plunges me into deep philosophical mode and I have sympathy for the poor souls who must deal with my sometimes week-long, sometimes month-long tendency to shift all conversation to questions about how others view issues related to either a. the distribution of wealth, b. dying, or c. both of the above. Somehow these topics tend to fall into the categories of things you don’t discuss at the dinner table along with religion and politics (maybe because they are related to both).

Blogs are probably like the dinner table. But sometimes, I think the avoidance of difficult topics only heightens the barrier to understanding them. This week, I read an interview titled “The Long Goodbye: Katy Butler on How Modern Medicine Decreases Our Chance of A Good Death.”

The interview stands in contrast to much of the positive media surrounding advances in medical technology, and indeed technology in general. There is a tendency to emphasize how simple technology makes human living. There is neglect in discussing how difficult technology makes human dying. But has dying become more difficult?

I agree that there are many ways in which technology has made 21st century living easier. Credit goes out to microwave ovens, smart phones, cars that park themselves and the FM radio toaster. We also have technology and trade that allow Pennsylvanians to eat bananas in March, farmers to extend the growing season and teachers to expand the classroom, reaching students on many different continents (shout out to CIDD’s MOOC). In an age with hyper-connectivity, increased accessibility to affordable technology and sophisticated means of communication, we have changed the many facets of human living.

In some ways we have gone from simple to simpler. In others, we have gone from simple to unforeseen complexity. We turned creating fire into a light switch. Simple. We turned talking to each other into waiting on phone lines, constant refreshing of email, Facebook poking. Kind of complex. In modern medicine, we have turned most infectious diseases into outpatient cases with simple pills. But the same science has also turned our experience of suffering from something human into something that we fear, heighten and prolong.

In the interview mentioned above and published this month in The Sun magazine, Katy Butler, journalist and author of Knocking on Heaven’s Door: The Path to a Better Way of Death, advocates for the Slow Medicine movement and expresses her thoughts on how our medical industry and culture has altered the experience of death in modern times. In the interview, Butler says “Death used to be a spiritual ordeal; now it’s a technological flailing. We’ve taken a domestic and religious event, in which the most important factor was the dying person’s state of mind and moved it into the hospital and mechanized it, putting patients, families, doctors, and nurses at the mercy of technology.” Butler’s perspective comes from her experience with her father, who after suffering a stroke and undergoing surgery to implant a pacemaker, lived an extended life that she felt only prolonged suffering.

The interview calls to mind the story of Vivian Bearing, the central character in one of my favorite plays, W;t by Margaret Edson (the film adaptation is on YouTube). In the play, Vivian Bearing is diagnosed with metastatic ovarian cancer. As an English professor, she seeks comfort in the poetry of John Donne, and slowly encounters a new understanding of death, which was once a motif she studied only in the classroom. “We are discussing life and death, and not in the abstract, either; we are discussing my life and my death […]” Surrounded by medical staff focused on the outcome of her disease from a research perspective, she becomes frustrated in how unromantic, how brutal and terrifying aging has become in contrast to its sometimes beautiful portrayal in literature. She is inundated with medical jargon and unfamiliar terms for stating how rapidly she is declining. The irony here is that even an English scholar is having trouble understanding the words we use to describe medical technology and medical decisions in modern hospitals. All her life she has enjoyed language games but facing death, Bearing says “Now is not the time for verbal swordplay […] / And nothing could be worse than a detailed scholarly analysis. Erudition. Interpretation. Complication. / Now is a time for simplicity. Now is a time for, dare I say it, kindness,” (p.69).

Technology has made many things simpler. Healthcare does not seem to always be one of them. However, the complex system that has developed in many industrialized nations stands in unusual contrast to medicine in many other areas of the world. People like Vivian Bearing or Katey Butler are facing problems that seem tragic, but I wonder if such tragedies come as a cost to the luxury of having access to any medical care. There are places in our world that have not yet achieved the simple. Many regions, in America, but especially abroad, lack healthcare and disease prevention measures we take for granted such as adequate access to vaccines, contraceptives and clean water. Can we find a balance between using medical technology to live better while also using it to die “better”? Can we distribute our medical resources and knowledge to maximize our potentials when living, while also understanding, recognizing and appreciating the fact that the beauty of living is in part due to its ephemeral quality.

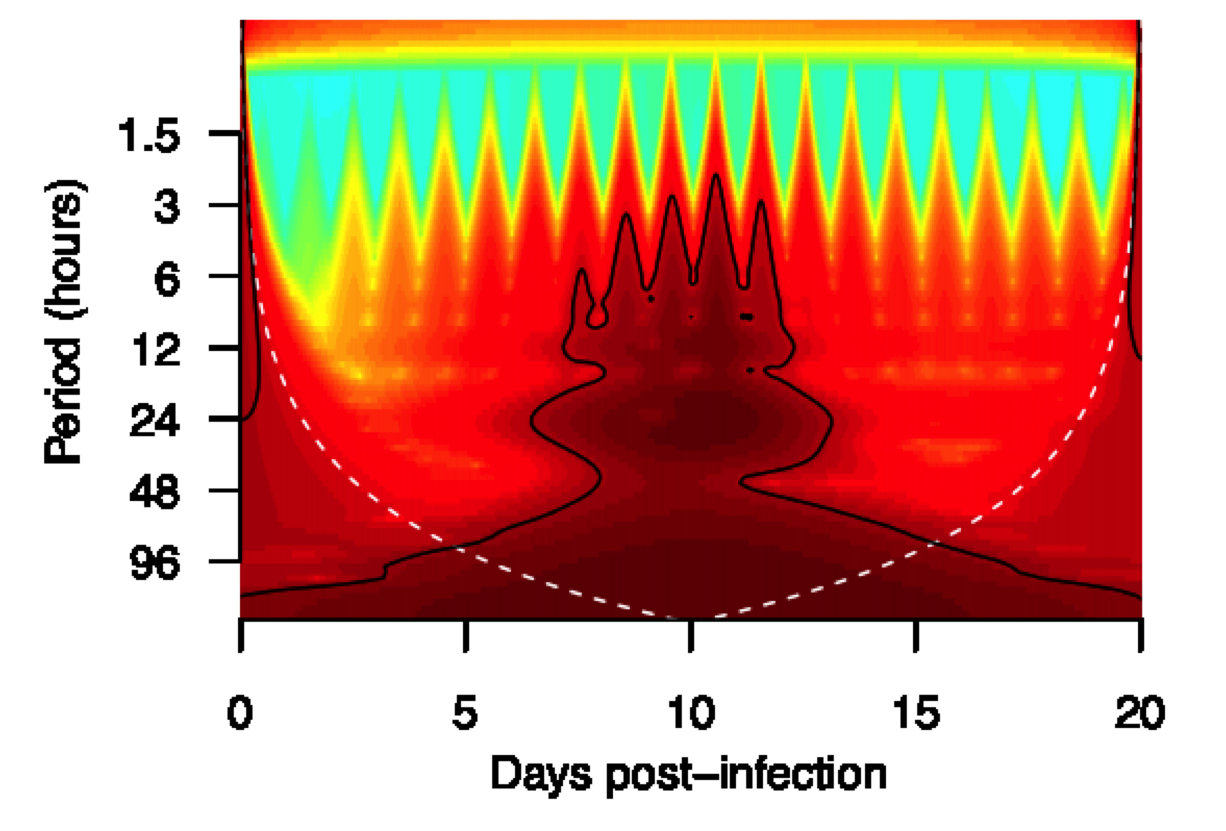

It seems like Butler and Bearing are exceptions. The diseases they have encountered (cancer, stroke, dementia and old age) are unlike deaths that the majority of people face in our world. In most places, isn’t technology making both life and death better? In the case of malaria, a disease that was easily resolved in America, the disease is still reeking havoc in the global scene. However, technology has allowed us to change this. With the use of antimalarial drugs and prophylaxis, we have caused a decline in the malaria death rate. Surely here modern medicine has increased our chance of “a good death”?

Malaria discussions in lab bring up many interesting discussions of problems related to drug resistance and host-parasite evolution but we less frequently discuss the interaction of these problems with poverty, infrastructure and how we die. Poverty and infrastructure seem like they could influence drug compliance, degree of drug pressure, and also, as Steve Lindsay discussed in his CIDD seminar, they influence the exposure to vectors that spread the disease. Are these things too simple or too complex to add to our focus?

I think technology has made us shift attention to the things we have made complicated, while the things we have simplified seem to be easily forgotten. Perhaps this is what happens to all things: complexity consumes more thought by its nature and simplicity is what allows things to drift from attention. In the American discussion of medical technology, we often lament its complexity — but is this because its simplicity (availability of pills, easy access to care, decline in infections compared to other nations) is easy to forget? Medical technology has changed how humans die, but I am not sure if it has made it better or worse, more complicated or more simple. In malaria, unlike the discussions of cancer, or diabetes or diseases of the industrialized world, technology seems like a force that enhances and improves quality of life rather than something that hurts our chances for a “good death.” Butler’s argument is a good one to consider in the modern American clinic, but one that needs to include an appreciation for what technology has done for global deaths due to preventable infections.

(On a side note, if you want to also read how technology has affected our ability to cook and my other thoughts on Butler’s interview, I blogged more extensively on the topic here).