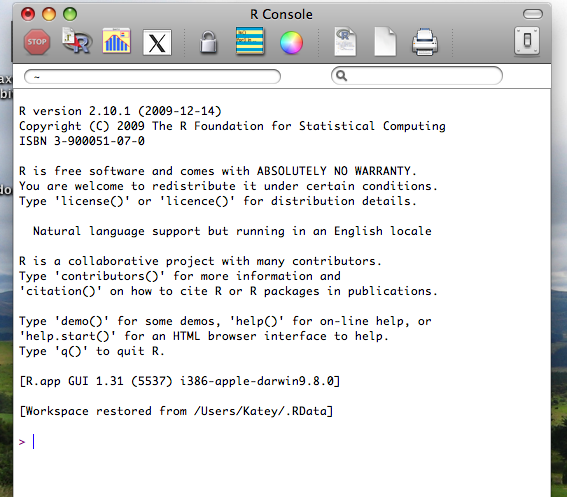

Recently, a member of the House of Representaives Committee on Science, Space, and Technology made comments suggesting that human females could control internal fertilization (clip). Italian courts don’t seem to understand how to interpret a P-value. (see Katey’s post ). Politicians continue to fight about whether global climate is changing, instead of making policy decisions about whether we need to do anything about it.

There seems to be a general lack of understanding about the facts science produces, the processes by which scientists arrive at those facts, and what role science should play in policy. I find this trend deeply troubling. Scientists have clearly failed to communicate how we conduct science, the methods we use to interpret results and the distinction between facts and opinions (interpretations of what our results mean) to policy makers. Attempting to bridge this disconnect seems impossible to me.

I have reached a place of complete frustration and think the situation might very well be hopeless. Clearly, I’m going to need help understanding the other point of view. I need to have a civil conversation with a Washington insider. I happen to know one and I think we can keep it civil. I actually love him. He is my dad after all.

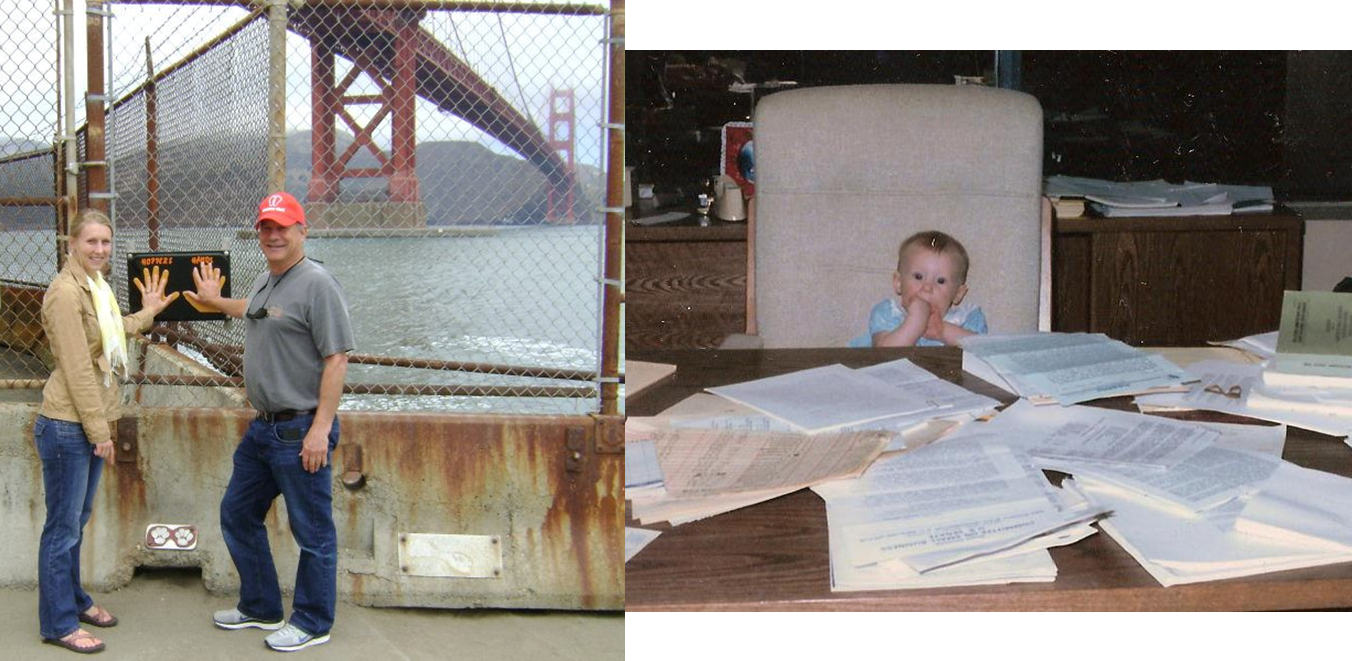

Left, My father and I agree on many things. Surely we can have a reasonable conversation about a "real" issue. Right, Me at my father's desk assessing policy briefs circa 1984. Clearly, I've already had enough!

My father, Tom Cator, has worked on “on The Hill” for the last 36 years. He began as a staffer for the U.S Senate and for the last 30 years has worked as a lobbyist across a broad array of industries. We had a fairly long conversation about science on the hill this week. Here are the key points that we discussed.

“Follow the money.” Money is part of the reason that policy makers often will argue or ignore facts. For example, if most of your state’s income is dependent on oil and gas, you are not going to go on the record agreeing these industries have contributed to global warming. “Politicians often don’t come in with an open mind. Their view is often based on who paid for it and what constituents think.”

“They will try to take you down”. I posed a question, “So say a group of scientists descended on The Hill. We went door to door and we offered to answer scientific questions”.

My father responded to this with a slight sense of panic in his voice, as if he was imaging me running through the Rayburn Building with a mosquito net, “That won’t work. First, they won’t have questions for you. Presentations have to be timely, or appear timely, in a political context. Second, if your facts don’t support their agenda, they may go after you personally, attempt to impugn your credibility. They will find someone to poke holes in your research.”

“Everyone has an agenda.” This was troubling. Facts are facts. Science is objective. You can’t just poke holes in research unless there are actual weaknesses. Why don’t politicians understand that? My father continued to explain that many times politicians think scientists are playing political games. “If you came to me with data, I would want to know what your agenda is”.

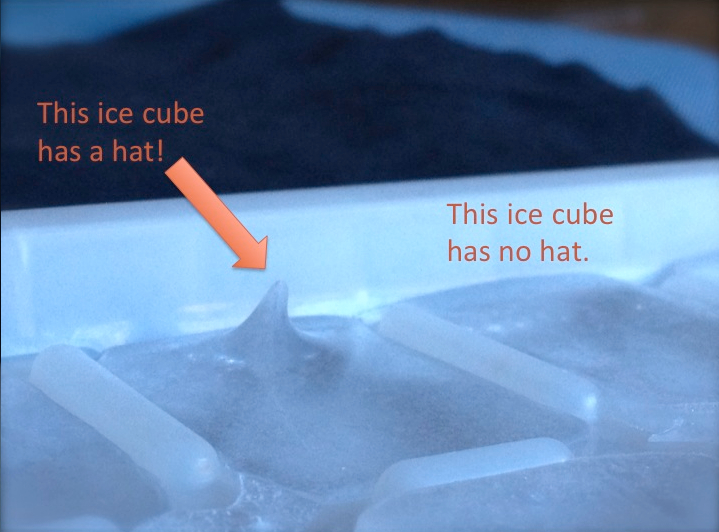

I countered, “Facts don’t have an agenda.”

Do they? Well, sometimes.

Over the last twenty years, there has also been a noticeable increase in “think tanks” in Washington. This term is broadly applied to many organizations, but some of the largest are privately funded entities. Many times politicians get their research from these sources. “Think tanks have to pay salaries and rent. It’s a business. Where do you think they get their money? Industry, organized labor, wealthy individuals, interest groups, and others.” my father points out.

“It is bleak and getting bleaker.” Over his career, Tom has noticed a disturbing shift in how business gets done in Washington. “It used to be that congressmen would get facts from lobbyists. A good lobbyist would approach a legislator with their case, represent all of the facts and facets of the issue, and then would explain why their policy position had merit. If an issue like climate change had come up 20 years ago there would have been multiple hearings with recognized experts. There would have been a long discussion about the facts. There is no longer a comprehensive look at the issue.”

There has also been a shift in how legislators define compromise. “It used to be you would find points on which you could agree and disagree and meet in the middle. Now, compromise tends to be ‘I don’t budge and you meet me here’.” This change in attitude has made debate, whether scientific, legal, or moral, stagnant.

“Nothing moves quickly”. “Policy does not change quickly. Within the next decade, Medicare is going to go bankrupt. They aren’t doing anything about that. You think they are going to jump on something like climate change? There is little effort to look at long term trends and how policy should respond. Statesmanship is needed.”

Acceptance of scientific findings is also very slow. “The system is rigged to not let real science percolate up, at least not in the short term”. We agreed that this was not necessarily a bad thing. Scientific debate and discovery moves very quickly. When we make policy decisions, we need to be very certain that the scientific debate is satisfactorily over.

“Strike back” At this point in the conversation I was not feeling particularly hopeful. How do we motivate these congressmen to listen and get something done?

“There has been a failure of science to address this issue.”

Politicians are in Washington to represent their constituents. If voters in their district care about something, then congressmen will care. “Getting the public, voters, and community leaders involved makes it much harder for a politician to walk away from facts”.

And then Tom got real personal.

“The academic community has fallen down. They don’t try to involve the public or policy makers. You live in a politically conservative county in Pennsylvania. What are you doing to educate your public on science?”

Caught off guard, I mumbled something about public lecture series.

“You can’t do it from 9 am-5pm. People work. What about continuing education at night? How about explaining how climate change is and will impact the farming industry in central PA?”.

I quipped back, “I don’t see how I can talk to people who don’t want to hear what I have to say”.

My father responded, “Find a reason for people to come and make it convenient for them. Go to a local high school science teacher and have her tell students, ‘Come to this thing tonight and you get extra credit, bring your parents and we will double it.’ Then present facts carefully and be as scrupulous as possible. Present work that has been rigorously peer-reviewed, and is complete and unbiased. Maintain objectivity and project a service. Engage them in a discussion.”

I do not feel anymore empathy for Washington, but I think this conversation did get my wheels turning. I have been going at this the wrong way. Changing the way science is viewed on The Hill needs to come from the ground up and it can start here with us. “The issue here is that we need to inspire constituents to become informed about science and communicate with their representatives.”

What if experts from CIDD gave an evening seminar series at State (or Altoona or Bald Eagle) High? What would the challenges be? Would scientists participate? Would anyone come? What topics could we cover? I have no idea how to answer these questions, but perhaps I should be thinking about them.