I just read (part) of this long blog post of someone (a mom!) who went through tenure track process (at Harvard!) happy and sane. She shared some (perhaps considered controversial) advise on how she did it. A great read!

The pursuit of happiness

I share an office with a social scientist/anthropologist and a recurring discussion since I started is whether striving for happiness should be our goal in life. She thinks not.

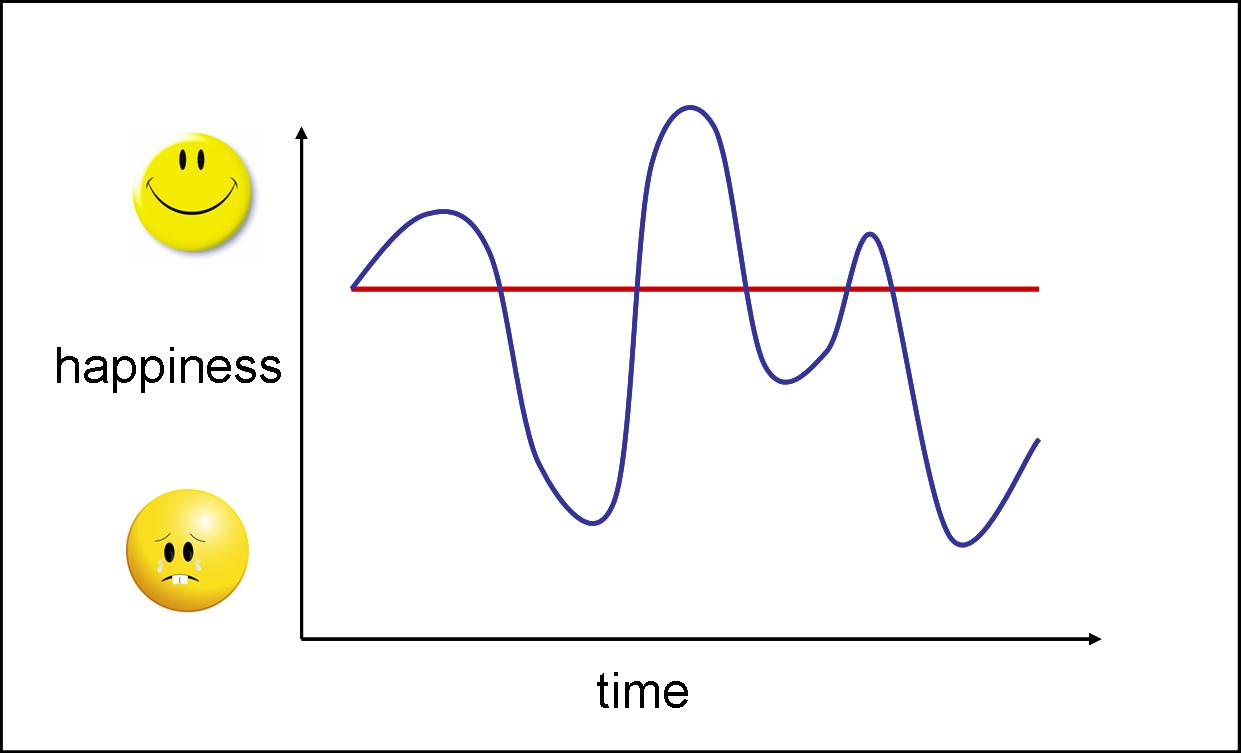

Odd. Surely everybody wants to be as happy as possible? She believes that having dips in happiness will allow you to have peaks too, and it is the peaks that are worth living for. Look at the chart to the right, which line would you prefer to be? Take the dips, have some peaks, but a lower ‘average happiness’? Or nice and stable, simply being happy. I think I vote for the latter.

Striving for happiness is a risky business. Being too happy all the time can actually be maladaptive, for instance leading to more risky behavior. In fact, research has shown that the pursuit of happiness can lead to negative outcomes. This seemingly paradox works as follows. The more you pursue happiness, the more value you put to happiness. The more value you put to something, the more disappointed you will be when your goals are not met. Result: you end up less happy then you were before. To make matters worse, a recent study has shown that by pursuing happiness, people felt lonelier each day. This is particularly true in our western world, where happiness is seen as a personal gain.

Conclusion, if you want to be happy, stop trying.

Summer Travels

At a time when information is so prolific and easily accessible at any moment, it becomes difficult to imagine how science was conducted even just fifty years ago. Any doubt on a biological mechanism, further progress on established theory, or brand new insights and discoveries can be easily unearthed by typing in a few key words into a search bar and producing thousands, sometimes millions of results.

But, here’s the downside. In our eagerness to know the answers as scientists, we are only too happy to start searching away for the information immediately. And I think that leads to a couple of problems during development of research ideas, especially for young scientists.

- Lack of creativity and ingenuity.

- Incorporation of incorrect information.

- Not enough time spent on analytical thinking early on in the research process.

I was lucky enough to spend a week in late June in Switzerland engaged in a course focused on training young PhD students on how to think about science. The mission: in a small group, conceive of an interesting research proposal, talk about it, write it up and present it in a week. No internet, books or papers. The mere idea of no internet might strike fear into the hearts of many and leave us fleeing for home during power outages at work, but I was amazed at how much everyone was able to accomplish. It was truly a brilliant, unique and informative experience.

It might be good to pause once in a while before hitting that search button.

Oh yeah, and then I went to Croatia and Bosnia for a couple of days after the course and that was fun too!

Is a vacation a vacation if you have to make up the work?

This past week I was in Montana for a buddy’s wedding and then Colorado for a RAPIDD meeting, all while letting everything else flounder. Today, when I got back to work, I thought it would be helpful to write a “to-do” list. Thirteen items later, I realized that I’m going to have a busy week. But look at me, “submit a blog post” is already crossed off.

Bioluminscent bugs part II

Like Lauren, I was also planning on blogging about fireflies this week but unlike Lauren, I didn’t see my first firefly until I was an adult. When you grow up in Miami like I did, the glowing insect that you chase after is the click bug Pyrophorus.

As I found out today, playing with Pyrophorus beetles is something that I have in common with Darwin. In the Voyage of the Beagle, Darwin writes “When we were at Bahia, an elater or beetle (Pyrophorus luminosus, Illig.) seemed the most common luminous insect. The light in this case was also rendered more brilliant by irritation. I amused myself one day by observing the springing powers of this insect, which have not, as it appears to me, been properly described.”

I also learned is that the Jamaican species Pyrophorus plagiophthalamus is polymorphic for the color of their glow, due to amino acid changes in the luciferase gene. Some bugs glow green, while others glow yellow or orange. The orange glowing allele appears to be recently derived and under positive selection (Stolz et al 2003), although gene flow between populations may be maintaining the color polymorphism (Velez et al 2006).

As far as I could tell in my brief scan of the literature, nobody yet understands what is driving selection on glow color in the beetles, although sexual selection and predation are the two obvious possibilities. In general, much less seems to be known about click bugs, especially when compared to the literature available on fireflies, but I suspect there might be equally intriguing evolutionary stories to be discovered.

Fireflies: A (completely terrifying) Summer Story

As a little girl growing up in Virginia, one of my favorite things about summer was watching and chasing the fireflies. They were clearly there to provide entertainment for children and tiny magical accents to humid summer nights. However, as I grew older I discovered that this beautiful display, like many romantic childhood fantasies, was a not at all what it appeared. What lay below was sex, murder, and drugs.

Both male and female fireflies flash to locate mates. The male signals first and then the female flashes back. There are over 2000 species of “fireflies” (which are actually beetles) and many of them will be flashing at the same fields. They manage to all use the same signal by evolving species specific intervals between the male and female flash. Using this species specific call and response, males are able to locate potential mates.

Females of genus Photuris can use two different signaling intervals. When looking for a mate she uses her species specific signal, but when she is looking for a meal she switches.

She starts flashing at the interval for a different genus of firefly, Photinus. Now, I want you do put yourself in this male Photinus firefly’s shoes (tarsi?). It is a humid July evening, the air is hot and thick. You fly out into the field looking for love. You flash and wait. She responds! You move close. You flash again and wait. Oh! Again! Finally you see her! She is lovely (a little bigger than you imagined, but no matter). You crawl over to her blade of grass and prepare to deliver your…BAM! SHE EATS YOU! Now that is a bad night.

As you are being devoured you might ask yourself, “Why?” Well the truth is this female is not only a siren she is a junkie and her drug resides in your flesh. Photinus fireflies synthesize large amounts of lucibufagins (0.5% of total body mass). These chemicals taste awful to birds.

Photuris fireflies do not produce this protective chemical. They obtain it by eating unfortunate Photinus males. The lucibufagins protect not only themselves, but also their offspring. The female passes a dose of the chemical onto her eggs and it deters predators that want to eat the eggs.

As a child I was enchanted by fireflies because they are beautiful. Now I’m enchanted (if not a little unsettled), but for a completely new reason. Now, when I look at a field full of those blinking lights I think of all of the complex interaction occur underneath. I think I like this story much better.

*For a more detailed description of the research that told us this story see Tom Eisner’s For the Love of Insects from which I got many of my facts.

The Leaky STEM Pipeline?

“Math, Science Popular, Until Students Realize its Hard”, says the Wall Street Journal and the National Bureau of Economic Research. The mentioned study is incomplete as of now and features responses from a select few colleges. However, the result still surprised me, as we often hear in our field how we need to work harder to sell our field and make it interesting to incoming students, particularly towards the end of their high school career. But they’re interested; we just can’t retain them.

But how many of them do we need to retain? Surely, it is important for our students to receive a better STEM education early on, as we rank 57th in the world in quality of STEM education, according to the world economic forum. At what point do we need to plug the gaps in the leaky STEM pipeline. Some, such as Representative Marcia Fudge (D-OH), chairwoman of the Congressional Black Caucus, suggests that improvements in STEM education need to be early on in the educational timeline. She maintains that not only will this improve retention of STEM students in the future, but will also bode well for increasing the number of minority and female students involved.

Rodney Adkins, the VP of IBM’s Systems and Technology Group and NAE fellow, however, says that there isn’t any part of the education or sociocultural timeline that can be pinpointed to solve the problem. He in fact seems to imply that enthusiasm for teaching and fostering interest in STEM fields seems to diminish throughout high school and college.

And yet still, there are some studies that suggest that we as a nation really aren’t short on STEM grads. Yes, our science and math education is dismal in the light of global competition, but in terms of sheer numbers and proportions, we aren’t lacking. At least according to a recent study by the Economic Policy Institute, a left-wing think tank seeking to tease apart issues of STEM jobs and immigration policy.

In December of 2012, the Obama Administration stated that they wanted to increase the number of STEM grads by 1 million in the next 10 years. My question is how? There’s language in their mission such as “identifying and supporting innovation in higher education”, but that is incredibly vague. Additionally, if the recent EPI study is more reflective of the current state of the STEM job market for recent college grads, will this goal (if fulfilled) tank the economy even more?

Biomimetics

A large part of my choice to specialise in disease evolutionary biology was (and is) a belief that it’s the most interesting part of biology. In turn most of my decision to become a biologist rather than another flavour of nerdy scientist was that I thought other forms of science were boring in comparison (and almost certainly harder). However, I do count myself very lucky to have friends who are equally convinced that their area of specialisation is the most interesting thing in the world and who are willing to patiently explain some interesting titbits in their attempt to convince me. I especially appreciate this when we are on runs as not only does it feel like I am expanding my mind while getting fit but it also has the great side benefit that if I time my dumb questions right I can get out of doing any of the talking on the uphill’s.

Something I learnt about recently while running with my friend Jay is biomimetics in the design of airplane wings. The fact that basic airplane design started with observing bird morphology is not surprising, what impressed me more is that NASA is still studying bird adaptations in order to further improve design and therefore fuel efficiency. Large birds such as eagles, hawks etc. have feathers at the tips of their wings which can curve up eliminating the vertical vortex created around the wing and reducing drag. Recently airplane designers have started using similar winglets with the same effect of reducing drag. This means fuel consumption is reduced and also that planes can have smaller wings while still generating the same vertical lift. There are also many other examples of where biology is being studied to help in aeronautical engineering. For example, North African desert scorpions have patterned exoskeletons with groves that help them withstand sandstorms so forceful they would strip paint off steel. Small grooves and bumps on the scorpions amour distribute airflow and reduce abrasion, something that again can be copied in the design of plane surfaces. I would like to say that I impart as much fascinating biology to my running partners but sadly I am normally too busy trying to breath.

It’s not just what you say, it’s how you say it

I’ve been taught science writing should be terse and pithy. In that spirit, here is a distillation of this post: Does pressure to be both concise and persuasive drive the development of biased terminology in science?

I started thinking about this a little bit last week when the term “evolutionary rescue” came up as an aside during Dave’s talk about genetic diversity and the rate of evolution. The basic idea with evolutionary rescue is if a population experiencing rapid environmental change has a lot of genetic diversity, then some individuals can adapt rapidly to the new conditions and “rescue” the population, preventing extinction (dependent on population size and the magnitude of change). I have become so used to thinking about evolution in a framework of parasites and drug resistance where the parasites are the bad guys that it wasn’t immediately obvious to me that in this case the drug resistant parasites would be the heroes that would “rescue” a declining parasite population under drug pressure.

There is a lot of jargon in science, some of which is certainly useful specific shorthand, and certainly some that adds unnecessary complexity, confusion, and arguably bias. I think part of this is storytelling, which I agree is an art and part of what makes science sticky and accessible to non-scientists. I attended a great lecture last year called “Making Tricky Science into Sticky Stories” and was convinced. Then again, is calling a single-celled organism “devious” (even if it’s a parasite) when it is just doing what every other life form on Earth is doing – living and reproducing – really necessary? Terms like evolutionary rescue give a positive connotation to rapid adaptation in changing conditions, and perhaps not surprisingly is used in the climate change literature where this is a pleasing and hopeful concept, but this concept is so closely tied to other rapid adaptations, such as in parasites for drug resistance, that it might be better just to spell out what we mean instead of making up a new term.

And now a subject about which I know very little: physics

If this article is to be believed, theoretical physics has entered a “now what?” phase. The Higgs boson turned out to be exactly what was predicted by the standard model that fails to address several key aspects of the known universe. The Large Hadron Collider didn’t turn up anything that would breathe new life into more comprehensive theories. And even worse, it’ll be another two years before new experiments can be performed. I can’t really fathom what this means to theoreticians, since I could continue to examine evolutionary theory in malaria parasites for many lifetimes. One of the main reasons I chose to work on these questions is that I am in no danger of putting myself or anyone else out of a job: for every question answered, many more questions arise, like the heads of a hydra. If each answer did not suggest new approaches or lines of reasoning, I’m not sure I could get out of bed in the morning.

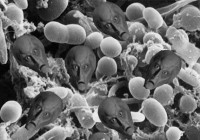

Theoretical physicists–being made of sterner stuff–will soldier on, and I look forward to descriptions of even more bizzare theoretical particles. I also take comfort that my field will almost certainly not reach a “now what?” phase in my lifetime. And in the meantime, non-theoretical (applied?) physicists have observed improbable particle behavior that I suspect could explain a huge amount of cross-contamination in laboratory settings, and a finding that itself suggests some rather disturbing modes of disease transmission…

Evolutionary Parenting

picture from evolutionaryparenting.com

I consider myself having two jobs: from 8 to 5, I´m a scientist, the rest of the time, I´m a mom. [Before you decide to stop reading, no, this is not a self-pitying my-life-is-so-hard-post, I honestly love both my jobs] Hence my excitement when I stumbled upon the following phrase: Evolutionary Parenting. Wow, I can apply my one job to the other? But then, what the hell does that even mean? Aren´t we all evolved to be decent parents? After all, if my parents, or my parents´ parents, or their parents´ parents were parenting fruitcakes, I wouldn´t be here. But no, all my ancestors were fed, protected from the elements, diseases and danger and socialized to the extent that they were able to find a mate to have babies again.

So, what´s this evolutionary parenting all about? In a nutshell, it is about chucking out all current cultural norms and go back to how parenting has evolved, such as breastfeeding until natural weaning occurs, ´wearing´ baby close to mom at all times like monkeys ´wear´ their babies in their first year(s) of life and sleeping together instead of the social norm of a separate cute baby room. Hmm… I use a cow to provide milk for my kids, push the youngest in a stroller, and they both happily sleep in their own rooms so I get some well-needed sleep to perform my two jobs.. I guess I am not an evolutionary parent after all. Yikes, am I reducing my offspring´s fitness?

Blog children! Blog! The machines are coming!

Whether it is running statistical tests in SPSS, doing a literature search online, or running assays in the temperature controlled Conviron, technology enables be to do my job everyday. This morning I learned about a new piece of technology and for the first time, it troubled me. Meet Quill. Quill is an artificial intelligence engine that will take raw data, analyze it, and write about it. Don’t believe that Quill could possibly do a very good job of this? Read its article on Forbes.com about Apple’s earnings.

On its website Narrative Science, the company that created Quill, explains how Quill takes charts and spreadsheets, “applies complex and sophisticated artificial intelligence algorithms that extract the key facts and interesting insights” and then …. “transforms them into stories”.

Did anyone else get a small chill running down their spine? One of the creators of this technology was interviewed as part of a piece on NPR’s TED Radio Hour. He believes people are uncomfortable with this technology because it makes them feel, “less special” since a machine can communicate in a way that we used to think only people could. I will say some of my apprehension about this technology is due to a fear of being replaced. Who needs post-docs when you can use Quill? (“The resulting content is as good or better than your best analyst, and is produced at a scale and speed only possible with technology”).

However what truly terrifies me about this type of technology is not the loss of my job. We are now creating technologies that can do things which we define as part of being human. I do not fear robotic replacement. I fear human atrophy. I appreciate that the current application of Quill is to analyze large amount of boring data and make is palpable to a board or CEO, but where does this stop? Will we remove writing requirements from majors in which Quill can pick up the slack?

In a recent New York Times article, Verlyn Klinkenborg (no algorithm came up with that surname!) discusses the steady decline in the number of English majors. These majors are not seen to produce people with useful skills. He explains, “..writing well is isn’t merely a utilitarian skill. It is about developing a rational grace and energy in your conversation with the world around you.” No technology, no matter how amazing, should excuse you from that conversation.

Storytelling

I love a good story. You know, the kind of story that you tell kids to instill in them a healthy sense of skepticism? My uncle – a poet and professor of literature naturally – used to tell these kinds of stories to me and my cousin all the time when we were kids. One day, I hope to tell these stories to my niece. It’s not that my family lies for the sake of lying; the lies in our stories are not malicious lies nor are they little white lies, they are big colorful lies told in the service of an entertaining story.

In contrast, I have an ethical obligation to be honest in my professional life. This obligation means that I can’t always tell the story I might want to tell, but storytelling is no less important as a scientist. Being able to tell a good story sells your science and advances your career; a good story, paired with good data hopefully, is what gets you into the top journals. The pressure to tell a good story can also lead to fraud, as it did with Diederik Stapel. But if we let the data guide us, storytelling is what makes the day-to-day of science meaningful. I don’t do experiments because they’re fun or intrinsically interesting, I do them because they’re essential to telling a good and honest scientific story.

Given that skepticism and storytelling are both integral to being a scientist, my conclusion is that if you want to turn your children into scientists, you should lie to them early and often. With any luck, they will quickly learn to question what they’re told, and they will know how to tell a good story. Everything else that they will need to know is already available through Google and Web of Science.

And lastly, just because I love a good story, I want to hear yours. What are the stories told in your family that aren’t necessarily true but are still a damn good story?

Are we supposed to be role models?

I just smoked my last cigarette. I said I’d wait until I finished the pack, but I ran the rest under water and crushed them in the sink.

I eventually came to the decision myself, but I’ve gotten a LOT of crap about my smoking habit since I came to grad school. Mostly because people don’t understand how I could be such a huge hypocrite; that is, I’m a scientist, and I, like most scientists, pride myself on my skepticism and reliance on evidence to make decisions. Yet clearly, there are absolutely no benefits of smoking cigarettes. None. No evidence points to any one pro, and there are decades and volumes of evidence that support a plethora of cons.

Which leads me to another question I get often; how can you have done four years of conservation biology, and then work in a lab that deals mainly in the effects of climate change on disease prevalence and transmission AND drive a massive tank of a vehicle that seats seven others and gets 14 mpg on a good day? Admittedly, that’s also insanely hypocritical. When I’m a little more established, I’ll purchase a more environmentally friendly car. And since that will be a while from now, hopefully hybrid technology and fully electric options will be more affordable for the average customer.

But my question is how much we really have to practice what we preach as scientists. We’re not as much in the public eye as politicians, but does it ever irk you that conferences for horrendous neglected tropical diseases in impoverished nations take place in lavish hotels, where we stuff ourselves with more food than we’d ever need? And how much should that bother us? Are we supposed to be role models?

So silly!

I have about one zillion other words that I need to write, so I thought I would just share some of my favorite ever words that someone else wrote in a scientific paper that I read. I encountered them years ago, in Hodjati and Curtis’ 1999 article, “Effects of permethrin at different temperatures on pyrethroid-resistant and susceptible strains of Anopheles.” I have had to re-read this paper a number of times, as you might guess based on the title if you remember anything about my work, and I’m always tickled to re-discover this tidbit of silliness:

“[…] mosquitoes were placed in a paper cup and, for their humidification and possible refreshment, a pad of cotton soaked with dilute glucose was provided on the top of the gauze covering the cup.”

Mentorology

If you want to make money as a poker player, read Doyle Brunson’s Super System. If you want to thrive as a samurai, read Miyamoto Musashi’s The Book of Five Rings. If you want to survive a zombie apocalypse, read Max Brooks’s The Zombie Survival Guide. But which book do you read if you want to learn how to advise PhD students? A brief internet search revealed no books on the subject.

I can imagine a few possible reasons why this type of book wouldn’t exist: 1) Nobody feels qualified to write it (it’s risky to make strong statements with only ~10 data points), 2) Nobody cares enough to write it, 3) Nobody is brave enough to be candid about past mistakes, 4) Nobody ever thought of it, 5) Nobody would publish it (because early faculty don’t have the time to read it, and experienced faculty don’t feel the need to read it).

My guess for the reason this book has never been written is because nobody who felt qualified to write it, had the motivation to write it, and was self-assured enough to tell anecdotes about his/her past shortcomings, ever thought to do it. Or the publishers didn’t think it would sell.

That or it does exist and I need to search harder.

Edit: Jessi brought to my attention the book At The Helm, which deals with this topic and other issues faced by young faculty. But I still find it interesting that there are so many books written from the student’s perspective, and so few written from the advisor’s.

Spontaneous Motor Entrainment (Science speak for “dancing”)

A couple of weekends ago I got the urge to go dancing and therefore proceeded to coax two of my friends to accompany me for a night of grooving or “flailing” (as Megan more appropriately calls it).

Is dancing uniquely human? This question certainly isn’t novel, being among one of many human characteristics that draws interest from the public and researchers alike who attempt to answer the fundamental question: how different are humans from other organisms?

Maybe you remember a couple of years ago the wildly popular youtube videos that surfaced featuring an African grey parrot and a cuckatoo who appeared to be moving in response to some tunes? Chuckles and slight snorts probably accompanied the majority of people’s reactions, but there were some scientists who watched with fascination and instead proceeded to ask “are these animals actually dancing?”.

Scientists took a systematic analysis of these two subjects and thousands of other youtube videos of animals “dancing” to provide evidence for a theory that has been previously suggested: only species that engage in vocal mimicry are also able to translate audio stimuli into coordinated motor expressions (entrainment). The biological reason for this may lie with basal ganglia modification (which has been shown to co-occur in avian lineages that developed a capacity for vocal mimicry).

Good work Science. Making the most of extracting information from otherwise time-sucking youtube videos to help answer evolutionary questions!

Why Managing Aliens vs. Superbugs is More Fun

After reading Andrew’s blog post expressing his bafflement over the amount of people who have viewed his TedTalk on the serious problem of drug resistance vs. his son’s video post from a popular play station game, Borderlands 2, I reflected on what I would rather watch, if offered a choice, and why. If I was going with my gut reaction (and if I didn’t know Andrew), I think I would rather watch his son’s video…sorry Andrew. Actually, in all honesty I would probably watch both, starting with his son’s video. This may be because I am a secret play station enthusiast, but I think there is something deeper here. Both videos discuss solving problems, whether it is more effectively managing superbugs or culling aliens. However, Matthew’s video represents solving a problem that we are ultimately in control of (if one gun doesn’t work, a bigger gun will), has little to no real consequences (oops, I died), and involves crazy beasts. Andrew’s problem is one we have much less control over (susceptible germs are a common pool resource), has very real consequences (a return to the era of pre-antibiotics – oops, we can really die in nasty ways), and involves invisible organisms (which in some sense is scarier). So, I think why many people choose to focus their attention on fluff like reality TV, fakebook, video games, and pure fiction is because there are many real world problems that are hard to solve, feel out of our control, and bottom-line are down right scary. Ignoring them, of course, will not make them go away or help inform decision making down the road, but I can understand the need to escape from reality. So I guess the remaining question is how to get people to engage on real-world problems? That, I do not have an answer for.

After reading Andrew’s blog post expressing his bafflement over the amount of people who have viewed his TedTalk on the serious problem of drug resistance vs. his son’s video post from a popular play station game, Borderlands 2, I reflected on what I would rather watch, if offered a choice, and why. If I was going with my gut reaction (and if I didn’t know Andrew), I think I would rather watch his son’s video…sorry Andrew. Actually, in all honesty I would probably watch both, starting with his son’s video. This may be because I am a secret play station enthusiast, but I think there is something deeper here. Both videos discuss solving problems, whether it is more effectively managing superbugs or culling aliens. However, Matthew’s video represents solving a problem that we are ultimately in control of (if one gun doesn’t work, a bigger gun will), has little to no real consequences (oops, I died), and involves crazy beasts. Andrew’s problem is one we have much less control over (susceptible germs are a common pool resource), has very real consequences (a return to the era of pre-antibiotics – oops, we can really die in nasty ways), and involves invisible organisms (which in some sense is scarier). So, I think why many people choose to focus their attention on fluff like reality TV, fakebook, video games, and pure fiction is because there are many real world problems that are hard to solve, feel out of our control, and bottom-line are down right scary. Ignoring them, of course, will not make them go away or help inform decision making down the road, but I can understand the need to escape from reality. So I guess the remaining question is how to get people to engage on real-world problems? That, I do not have an answer for.

Dozing for data

Apologies if this is an abuse of the blog, but here we go…

In the most Tom Sawyer-ish way I can muster, I invite you to come catch up on all those papers you’ve been meaning to read/think deep thoughts/take a nap over at the Insectary. I’m testing some new bednet technologies and would love some help!

In the most Tom Sawyer-ish way I can muster, I invite you to come catch up on all those papers you’ve been meaning to read/think deep thoughts/take a nap over at the Insectary. I’m testing some new bednet technologies and would love some help!

It seems like a pretty sweet deal to lie around all day collecting data. Unfortunately, there are only so many hours in a day that I have available to essentially be mosquito bait, and lots more data I would like to gather.

If you have some time (45 minutes minimum) where you could just as easily work (or not) while lying on a pretty comfy mattress under a net, send me an email to let me know you’re interested and when you’d like to come on over. I’m planning to start a sign up sheet for napping. You get to climb under the net, I release some mosquitoes in the room with you (don’t worry, you’re under the net, and this project is SEPARATE from the P. falciparum work…) and after an agreed upon time I come back and collect them. We can start an in lab competition to see who can attract the most mosquitoes.

Vegan bacon (it’s not an oxymoron)

I had a craving for vegan bacon earlier this week, so I marinated some tempeh using one of my favorite recipes and took the leftovers as lunch a couple times this week. In my non-random sample of three omnivores, all were curious about the substance residing on a bed of spinach, all were deeply skeptical about the concept of vegan bacon, all three really liked it once they tried it, and two demanded the recipe. (Hint: liquid smoke is key.) Nicole suggested that I call it marinated tempeh so as not to put off carnivores, but upon reflection, I’d prefer to challenge people’s preconceptions about bacon. Following on an earlier lunch conversation, all too often we get disappointed by something that is actually really good because it’s not what quite what we were expecting (e.g., negative results that challenge our world view, vegan desserts, etc.).

On a related note, Bill Gates is investing in egg-substitutes because it’s questionable whether animal-based foods are going to be a sustainable enterprise at our current rate of population growth. The potential environmental consequences are worrisome, but I was also disappointed to hear that none of the current egg substitutes on the market can make a viable scrambled eggs-equivalent. (Though they note that studies suggest that people can’t tell the difference between baked goods made with and without eggs, in line with my own experimental results long those lines.) Apparently the non-eggs tend to crumble instead attaining the coveted bouncy-ness of real scrambled eggs. At least until chemistry finds an answer, I suspect that the trick might be to recondition our expectations of what scrambled eggs should be.