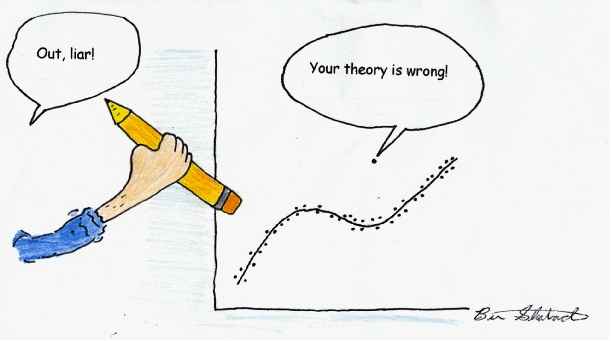

One of the questions that every theorist stresses over when constructing a model is how complicated the model should be. The correct answer, of course, is that the model should be exactly as complicated as it needs to be, but no more.

Try this thought experiment. Look at a glass of water sitting on a nearby table or desk. Imagine pushing the glass over the edge, and try to follow the trajectory in your head. My guess is that you can visualize this process fairly well. You might even be able to picture the shards of glass scattering when it hits the floor, or the shape of the puddle that the liquid ends up making.

We can picture this process so clearly because in our lifetimes we have seen many things fall. Sometimes the object was a glass of water from a table, sometimes it was a pencil from a desk, sometimes it was an apple from a tree. And using these observations, we developed a model that allows us to predict how things will fall before they even begin to move.

In the thought experiment above, a glass of water was pushed from a table. Does the trajectory of the fall change if the water was replaced with beer? What if the liquid was dyed green? What if the glass was dyed green? If the goal is to predict the trajectory of the falling glass, these details don’t matter, and they can be left out of the model. Interestingly, leaving these details out of the model makes the model more general, and in turn more useful. I mean, how often do you push a glass of green water off of a table? What good would that model be?