A key indicator that someone is going to grow up to be a scientist, I think, is a propensity to look at the world and ask “What the…?!?”.

Having a live-in physicist has proven extremely useful for satisfying my (often fleeting) curiosity about lots of things, e.g., what is electricity? Why can’t something go faster than the speed of light? Or — stealing something from Katey’s curiosity — what would happen if there was no moon?

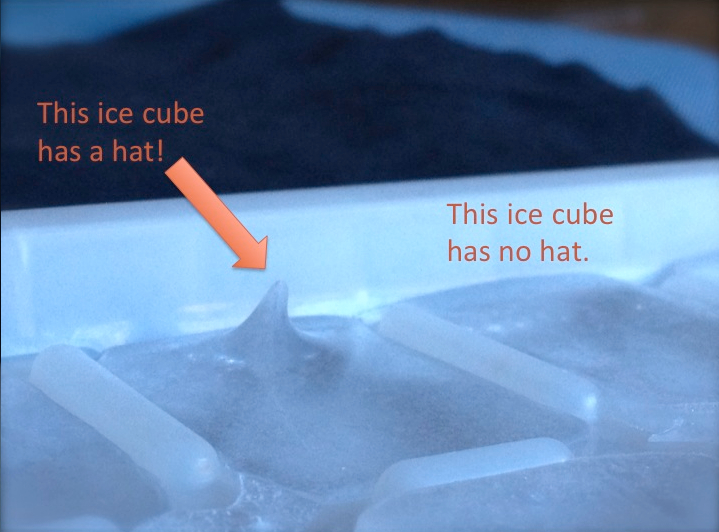

I was therefore surprised when my physicist couldn’t explain my recent curiosity, stemming from a bizarre finding in my freezer (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A picture of my actual ice cube tray and most recent batch of ice cubes. About 83% of the ice cubes in this batch were as expected (hat-less). The remainder had these astonishing little hats.

What the heck was this hat doing on my ice cube?!? I thought this wonder of science was sufficiently interesting to bring it up at lunch with my labmates. They offered a bunch of hypotheses for what could cause an ice hat. Maybe something was vibrating underneath the ice cube tray, or something was dripping from above it. Megan had the most inspired idea: could the formation of the ice hat have something to do with the purity of the water? The water in State College is notoriously hard, containing a lot of calcium. She thought that if I hadn’t filtered my water before freezing it, these impurities could provide a substrate around which the ice crystals could form. Turns out Megan was right, only in reverse.

Water with impurities does form ice around those impurities, but it also forms ice relatively slowly. Without impurities, water freezes so quickly that the water beneath the surface begins to freeze before the surface (which starts freezing first) is frozen solid. Since water expands as it freezes, the developing ice below pushes water up through the part of the surface that isn’t yet frozen. The surface of this emerging water freezes quickly too, so that as the water is pushed up and through a hole in the surface it freezes into a tube, which funnels more water upwards. This process generates what is known as an ice spike (though, I prefer the friendlier ‘ice hat’). The faster the water freezes, the taller the spike. With impurities, the water freezes slowly enough that the surface is frozen shut before a spike is made.

Apparently physicists could have answered my question, I just asked the wrong one. Two physicists published a paper in the Journal of Glaciology on this exact topic. Academia may be the only place where people get paid to satisfy their “what the…?!?” curiosities and that is pretty awesome.

Ice spikes are also pretty awesome. Make ice cubes from filtered water; impress your friends!